This morning, I long most of all to see the faces of Palestinians, hear their voices. Mothers and daughters are dying in Gaza, children routinely tortured in jails, everyone starving as the US/Israeli war machine restage their origins in genocide, laying bare the roots of western culture. What a relief to find Kamal Aljafari’s A Fidai Film (2024), winner of a prize at the Visions du Réel Festival. According to my Iranian pal Farzaneh, “fida’ī” in Arabic means “sacrifice” or “martyrs”; freedom fighters. She reminds me that Fida’i is the national anthem of Palestine.

Terra nullius means “nobody’s land”. It’s an old European term that provided legal cover for stealing land abroad. Canada, Ireland and Australia were among the many territories seized by colonizers who claimed that no one was there. Israel was created as part of the same legacy of European land grabs; its version of terra nullius was the slogan “A land without people for a people without land”. This catchphrase offered justification for the moral rot of the apartheid state. In order to erase the native population of Palestinians, it was necessary not only to tear down their towns and villages and build settlements over them, but also to bring the war to their memories, their archives and libraries, to remove every trace, as if they had never existed. This has been central, for instance, in the work of Israeli archaeologists whose “research” continues to justify Palestinian expulsion, as Maya Wind details in her must read Towers of Ivory and Steel (2024).

Kamal’s movie shows the looting of the Palestine Research Center in Beirut (established in 1965) during the Israeli occupation of Southern Lebanon. Parts of this collection, along with others of an even more mysterious origin, have been sourced by the filmmaker to create a counter-archive that refutes claims of “nobody’s land”. These precious images (still possible in this moment of digital overload) return to a country of ghosts and allows Palestinians to walk the streets they were born in once again; here is a man picking olives, children eating oranges. Each of these everyday moments is an anti-colonial gesture that stands in the face of overwhelming efforts of erasure.

A Fidai Film begins with shots of the Mediterranean Sea, with British war ships parked offshore, the sun enhanced by a red orb that shimmers and threatens in an otherwise black-and-white image, a reminder perhaps of an empire whose sun will never set, because its historical cruelties are a central piece of the global network that distributes advantages (money, goods, knowledge, technology) and disadvantages (debt, pollution, knowledge gaps). [1]

We see street shots of Jaffa during the British “Mandate for Palestine” (1920-1948), including the Falastin newspaper office, begun in 1911, one of the two most important Palestinian newspapers. Jews and Palestinians mix freely on the street. Keffiyehs, kufis and European suits join in a city where walking remains the chief mode of transport. When the occasional automobile rumbles by, it carries the threat of new war technologies that would fill these streets in the decades to come.

This scene is immediately followed by an extended passage from a UN film, made in Palestinian refugee camps after the Nakba (“the catastrophe”—the systematic expulsion of 750,000 Palestinians from their homes after British colonizers were replaced by their Israeli successors). Arabic script appears over the images, redacted by a thick red scribble. Just like the opening images, the redactions are the only element of colour. [2] Now, the people we saw walking on the streets—shop owners and school teachers—huddle in tents in the middle of the desert. Children are taught in “school,” sitting outside in the desert while a teacher uses a stick to draw in the sand. When the camera returns to Haifa, the streets are empty, the buildings deserted. There are only shadows walking across walls, or two children glowing red in a broken archway. Blood memories of the erased.

Ghassan Kanafani (1936-1972) is one of the film’s central figures, though never shown (he speaks in his absence, another haunting the film embraces). Statesman and revolutionary, Kanafani remains a giant of Arabic literature, his books retain a global audience. He was murdered along with his teenage niece by a car bomb planted by the Mossad (Israeli intelligence) in 1972.

Four text excerpts from Kanafani appear as intertitles over sequences across the film. In Kanafani’s short story Letter from Gaza (1956), a father describes how the entire territory was “shaking with grief” for the lost leg of his daughter. “A grief that was not confined to crying—it was something like reclamation of the severed leg!” Later, an excerpt from Returning to Haifa accompanies shots from a car moving through emptied streets and rubble in Haifa. In Kanafani’s touching novella, a couple returns after the 1967 war to search for their missing baby. These wounded texts are personal and political, testifying to the embodied cost of occupation.

Kamal’s lyrical image flow mixes chronologies and disaster sites, returning to the origins of the Israeli state, stepping inside Palestinian refugee camps (Bedoaui Camp; Baqa’a Camp, the largest refugee camp in Jordan; Qalandiya Camp in 1957), but also including extended passages about Palestinian life in Lebanon after Israeli invasions in 1978 and 1982.

Again and again, the filmmaker returns to Haifa, the city of his father and the subject of three prior films: The Roof (2006), Port of Memory (2009) and Recollection (2015), “a haunted triptych of his paternal city”. [3] We catch glimpses of the Bahá’í Gardens, the Al-Jarina Mosque in Wadi Salib and the Alhambra Cinema (opened in 1937), which became a key Palestinian cultural centre. An alternating current of crowded streets and rubble, a city of Palestinians and a city of disappearances. An Israeli man in a long coat and suit, surrounded by soldiers, celebrates amidst the ruins they have created, proud killers in a city remade in their image. The camera arrives in the aftermath to create victory trophies, souvenirs of war.

Eschewing the universalist language of the colonizer, this meticulously constructed film is stuffed with codes and signs legible most of all for those familiar with the homeland, the intimates of occupation. Here is one example. In West Beirut, a massive car bomb set by the Israelis outside a building of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) devastates the city, citizens rescue survivors as blood and bodies fill the street. This TV report is narrated by David Smith for the British news service ITN, French paratroopers are part of the rescue effort, both reminders of the colonial powers that carved up the region after the Ottoman Empire was defeated, planting seeds for the unending conflicts left in their wake.

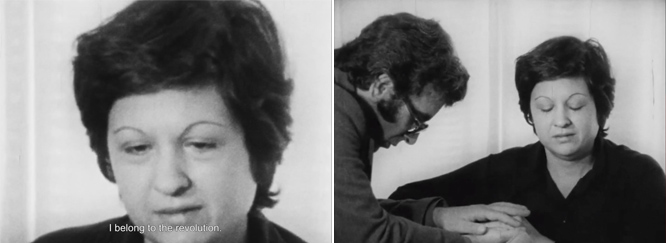

A conventional documentary might lay out reasons why Palestinians were driven into Lebanon, but instead, the next scene delivers us to an intimate domestic interior. Hind Jawhariye’s face appears in close-up, she is visibly distraught and struggles to speak. Instead of words, there are guttural rasps and broken syllables, a language before language. What words could touch her loss, this impossible death? It is not until her fourth appearance that she can speak of her photographer son, who told her, “I don’t belong here. I should be with the fighters. I belong to the revolution”. [4]

Her testimony is intercut with an Israeli feature film (provenance unknown). A young blonde couple wander across a deserted seaside, as if they were the last ones left in the world. They are the embodiment of the new Jewish state, Aryan masters, white innocents. Their enigmatic dialogues in the ruins carry ghost memories of the slaughter that has made their new Eden possible.

The filmmaker has digitally painted out their faces, redacted them. They wear blood masks of a history their new lives are built around forgetting. The broken mother who preceded them cannot forget, just as they cannot remember. The red-faced couple appear “in the place of her son,” on his land, which has become “no man’s land” (terra nullius), as if colonizer and colonized belonged to the same haunted family.

How has the filmmaker created an epic work of archival salvage that is suffused with such intimacy, such a deep and fathomless feeling? Palestine is a country that is not a country, producing poets by the score, and now digital poets who create marvels of cinema out of the ongoing catastrophe of apartheid and colonial ruin.

[1] Reconsidering Reparationsby Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, 2022

[2] The colour mattes were created by digital magician Yannig Willmann. How exquisite and rare it is that an artist’s movie features a VFX credit.

[3] Ghosts Beneath the Surface: Remnants and revenants of Palestine in the Cinema of the Interiorby Robert George White, 2020

[4] “Hind is the partner of Palestinian director Hani Jawhariye. Hani was originally from Jerusalem, but was displaced to Amman, Jordan which he left to join the Palestine Film Unit of the PLO in Beirut at that time. He died while filming a battle during the civil war in Lebanon. The man holding her hand is Mustafa Abu Ali, one of the main filmmakers of the Palestine Film Unit. Hind Jawhariye is still alive, living in Amman.” Flavia Mazzarino

*

Mike Hoolboom began making movies in 1980. Making as practice, a daily application. Ongoing remixology. Since 2000 there has been a steady drip of found footage bio docs. The animating question of community: how can I help you? Interviews with media artists for 3 decades. Monographs and books, written, edited, co-edited. Local ecologies. Volunteerism. Opening the door.

|

envoyer par courriel |

| imprimer | Tweet |