Hoping to write this column, I reached out to the film’s director, Jacquelyn Mills, for a link to her feature-length documentary Geographies of Solitude. She suggested I check it out at a festival in Montreal, 500 km away. I hadn’t realized she was offering me a pilgrimage. The Hajj, the once-in-a-lifetime journey to Mecca, remains one of the five pillars of Islam, in other words, an abiding feature of contemporary life. And not incidentally, treks like this are one of the few activities that Werner Herzog recommends as a substitute for film school. But I had grown too used to the borderless accessibility of images, a democratic flattery assuring us that every recording can be instantly accessed.

I used to wait months, even years before I could see a desperately sought-after movie, poring over frame grabs in Parker Tyler’s book Underground Filmor back issues of Cantrills Filmnotesthat were precious simply because they mentioned movies and artists I might never get to see. Participating in artist-movie culture meant showing up for screenings of work that would, for the most part, never appear again. And behind the lure of the present, each of us carried a “most wanted” list of cultural icons that existed only as rumours, a throwaway sentence at the end of a review. Because we couldn’t afford to travel, we made pilgrimages in time.

When fall arrived, the Planet in Focus Festival in Toronto offered another chance to see the film. It turns out the main character is an island. Sable Island is a skinny landslip, 42-km long and as little as 2-km wide in some sections, located in the North Atlantic, south of Halifax. A single tree grows there. One house. Mostly, it is filled with sandy beaches where grey seals hang out, and 500 wild horses roam around. Can an island make a film? If it could, what would it look like?

Film buried in horse shit and developed in yarrow.

Splicing marine litter and plant matter onto film.

Horsehair, bees and sand exposed to starlight, developed in seaweed.

The island is filled with a wind that thunders across the ocean with a terrifying and unrelenting roar, or else shimmers in the goldenrod which rub their stalks together in a haptic delirium, like an orchestra of soft brushes. Vast waves reshape the coastline while, in the interior, patches of wetland draw thirsty horses. Just like the characters in a feature film, long scenes showcase the beauty and terror summoned by these natural forces.

And while it is a commonplace, even in docs that are dedicated to nature world splendours, to juice up the experience by parachuting orchestras into the middle of old-growth forests, or at least big band jazz ensembles into the Arctic; here the artist is dedicated to the sounds of the island itself. She brings an array of unusual microphones, allowing her to listen underneath the waves, or deep into the life of plants and rotting timber. If the impulse is to provide a fuller spectrum of the you-are-there documentary experience, the aim throughout is pleasure, the sheer delight in hearing the soft crackling of underwater life, the haunted seal murmurs.

Recently a small short-haired terrier came to visit, and we quickly became inseparable. One of the things that Drake (sorry, I live in Toronto, every dog is named Drake here) likes to do is watch movies. He doesn’t sit back and analyze, he watches with his whole body, he jumps up to alert minor characters to immanent dangers, he paws at the screen, or cowers beneath a pillow. In short, Drake is the ideal audience for artists’ movies. I thought of him while Geographies took me through its sensorial thrill ride, because I felt I was hearing and seeing with my whole body, the bass notes of the contact microphone ringing through my diaphragm, the slow-motion shuffle of a caterpillar as it reaches its way from one flowering plant to its neighbour making my fingers tingle.

Mills’ dream camerawork is a reminder that, in most of today’s movies, particularly in artists’ movies, there are no pictures. Sure, recording machines are pointed in the direction of the action, but with little understanding of how a picture is made. Imagine our mobile phones offered not a camera, but a paintbrush. The result? Everyone’s a painter, but few know how to paint. In fact, it becomes an environment where learning how has never been harder. Why bother?

The artist brings the heat from the opening shot. A staggering night sky fills with stars that never existed before. Stallions nod in the sunset, every muscle drenched in the good light, later seals bob in the open surf. On this island, everything is alive, and the camera is also a living and independent body. It doesn’t stare or follow its subject, but engages in a dialogue, a conversation of seeing and being seen. The camera acknowledges the presence of a seal, then drifts slowly past, across the windswept beach, coming to rest in a hollow where a placenta lies. Such a tender way to say “Mother.”

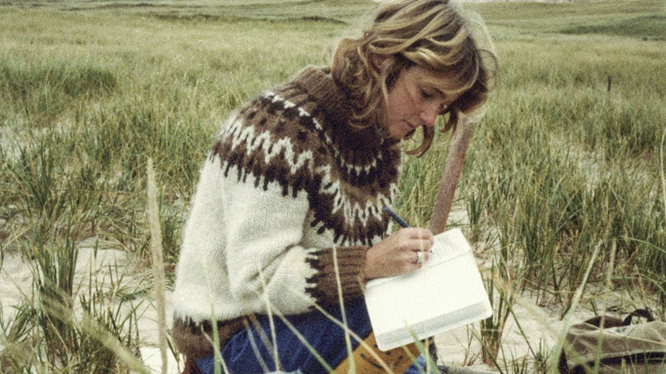

The main character in the movie, the loneliest woman in the world, is Zoe. The artist never pretends that Zoe is her best friend, she doesn’t whip her camera up into Zoe’s face and fill the screen with it. Instead, she approaches her the way you would approach an animal you find on the street, slowly, with care, allowing this foreign creature to take her in and establish a mutual safety zone. In fact, for most of the movie, we don’t see Zoe’s face at all, not until the closing sequences, when some boundary between the two of them drops, though it never leaves entirely.

Zoe Lucas is the only human on the island. She’s spent nearly all of her adult life there, alone. “It turns out my life is Sable Island,” she says. “That’s all I have. That’s all I do… It’s been really super interesting and super rewarding and engaging and fulfilling to be here, but I lost track of everything else.” All of the lives she could have had, the relationships most of all, the family and friends, the lovers and comrades, all have shrunk away so that she could dedicate herself to the ongoing work of the island as a self-taught naturalist.

What isn’t she doing there? Thanks to Zoe, every horse on the island has a name, a family history, a catalogue of relations, diet, injuries and behaviour. There are hundreds of pages of notes about the horses, like a journal chronicling the life of a village.

Thousands of specimen jars house insects: beetles, spiders and centipedes. Each jar is carefully labelled, recording many never-seen-before species. Meticulously kept notes are attached to each of these treasures.

And finally, there is the news that the ocean brings in, carrying plastic garbage from as far away as the northern coast of Africa, from across Europe and North America. A lot of it turns out to be party balloons, which Zoe carefully cleans and separates, and then notes where they are from, so that she can determine what is household waste and what is the effluence of industry. She sometimes finds addresses, even hand-written missives, and, when she does, she writes back to tell them where their garbage has wound up. Her balloon collections appear unending, the level of detail she musters while cataloguing evidences a scientific diligence that is both awe-inspiring and pathological.

The filmmaker sometimes offers hesitant questions in her strangled, little girl voice. Near the end of the movie, she asks if Zoe will accompany her to record some sounds. The scientist replies, “But you don’t really need me for that, do you?” The artist says quietly, “But it would be nice to have company.”

When I was a kid, I asked my father about the third dimension. I had seen the term in a comic book, but had no idea what it meant. He drew the stick figure of a man, then drew a box around him. “You see? This man is in prison, there’s no way out.” He drew arrows in every direction. “But if he lived in three dimensions, he’d walk out of the jail this way,” Dad assured me, bringing two corners of the page together, so that the man bulged out of the drawn square around him.

When I try to understand the term “posthuman,” I think of my father’s explanation. Imagine a world where humans are not the centre of it all. I’m still so drunk on the Kool-Aid, I can’t really picture it. But here, in this movie, there is a glimpse of another world. Sable Island means that goldenrod is more important than your mother. Horse shit is more compelling than having sex. Collecting plastic is more fulfilling than a best friend. As the climate scientists have made clear, we are hurtling towards the end of the human experiment. But before the very end, there will be some who will do literally everything they can to stop that from happening. They will dare not simply to imagine that another world is possible, they will live in that world. Viva Zoe Lucas!

*

Mike Hoolboom began making movies in 1980. Making as practice, a daily application. Ongoing remixology. Since 2000 there has been a steady drip of found footage bio docs. The animating question of community: how can I help you? Interviews with media artists for 3 decades. Monographs and books, written, edited, co-edited. Local ecologies. Volunteerism. Opening the door.

|

envoyer par courriel |

| imprimer | Tweet |